「米国の科学と軍産学複合体」追加情報 [仕事とその周辺]

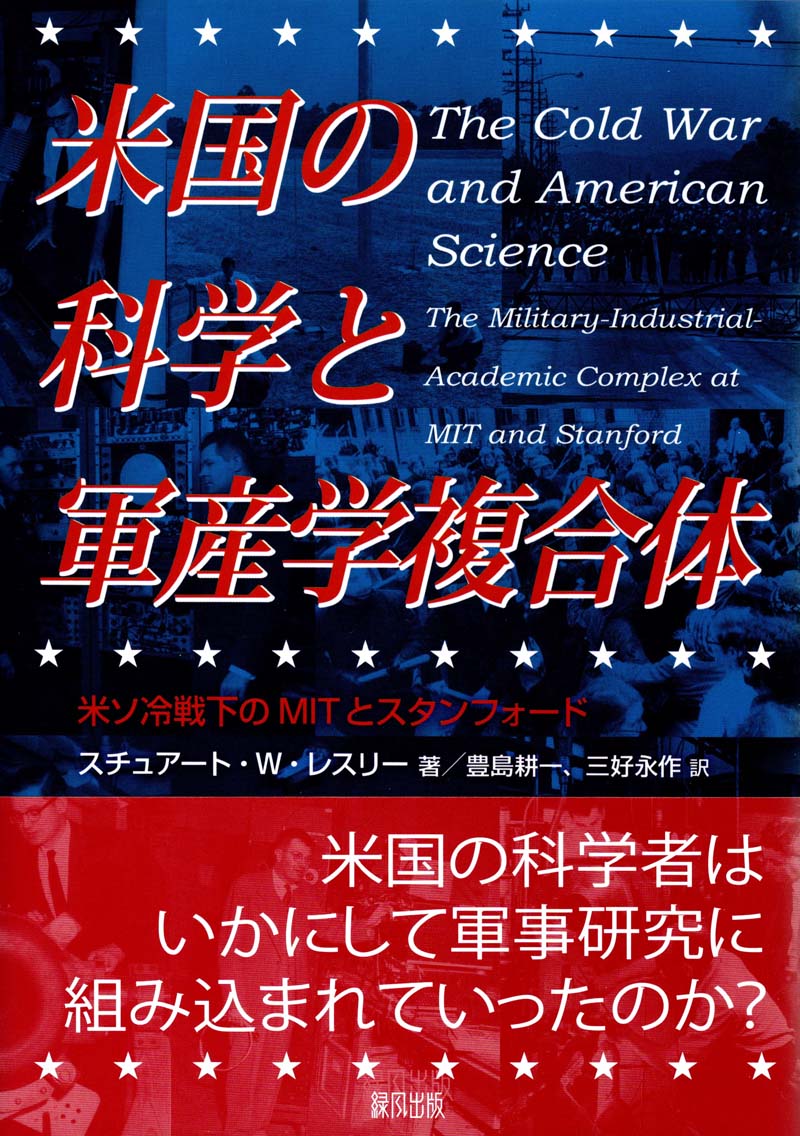

先にお知らせしました翻訳書「米国の科学と軍産学複合体 ―米ソ冷戦下のMITとスタンフォード」に関する追加情報を、このページでお知らせします。

(原書タイトル:The Cold War and American Science ―The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford, 著者:Stuart W. Leslie)

全国の図書館101館で所蔵(2022/1/18現在) 原著者序文の日付を2に追加しました。

原著者序文の日付を2に追加しました。

目次

1.事項索引の追加(すぐ下)/the addition to the subject index

2.日本語版への序文のオリジナル(英語)/preface to the Japanese edition in English

3.「3月4日のマニフェスト」の日本語訳(リンク)/Japanese translation of the 'March 4 manifesto →直接ジャンプ

4.組織や人物の関係を図式にしたもの(リンク)/relationships of organizations →直接ジャンプ

5. 訳者あとがきの英訳/English translation of the translators' afterwords

訳者あとがきの英訳/English translation of the translators' afterwords

6. 帯の英訳/English translation of the phrases on 'obi'

帯の英訳/English translation of the phrases on 'obi'

-------------

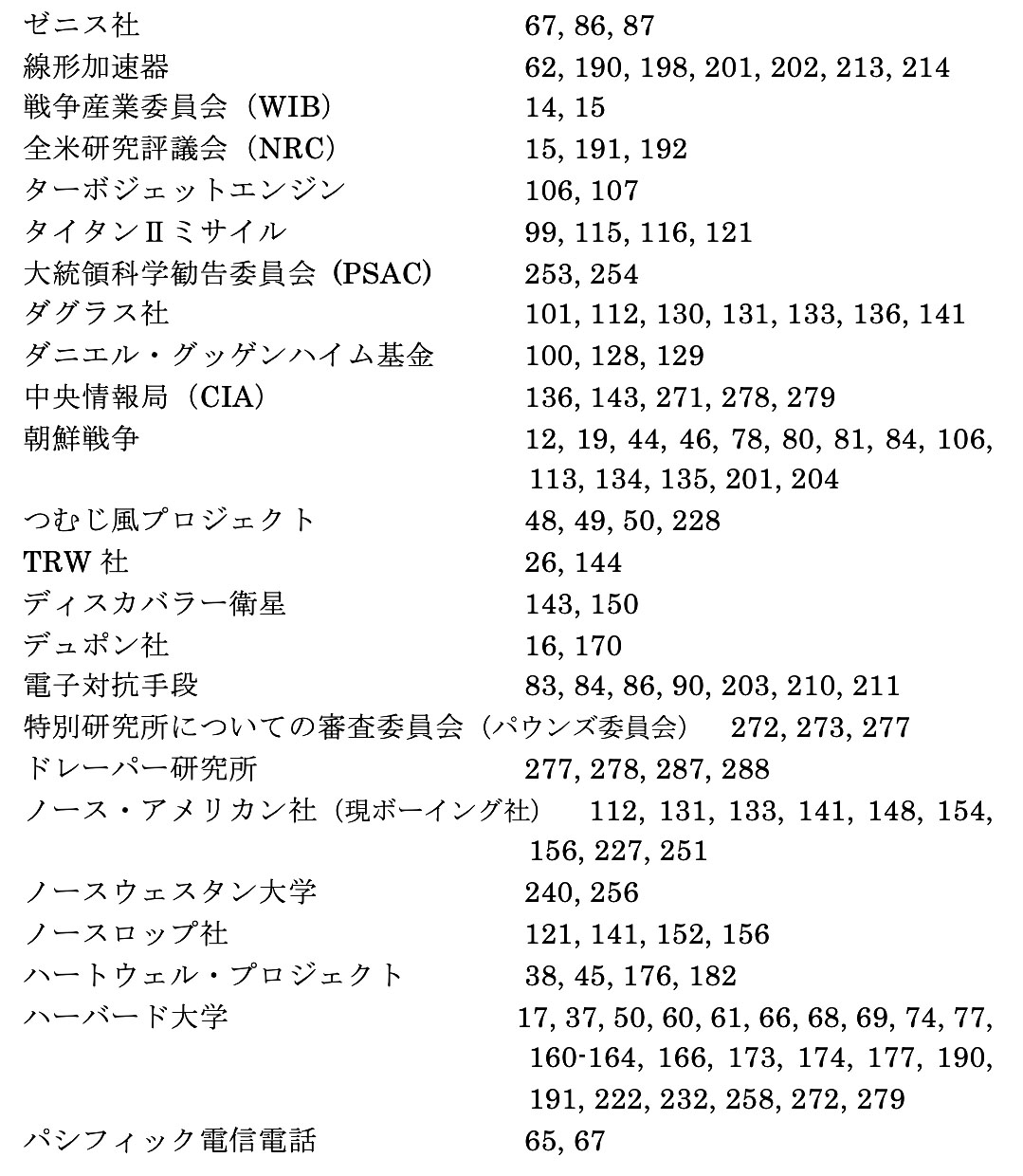

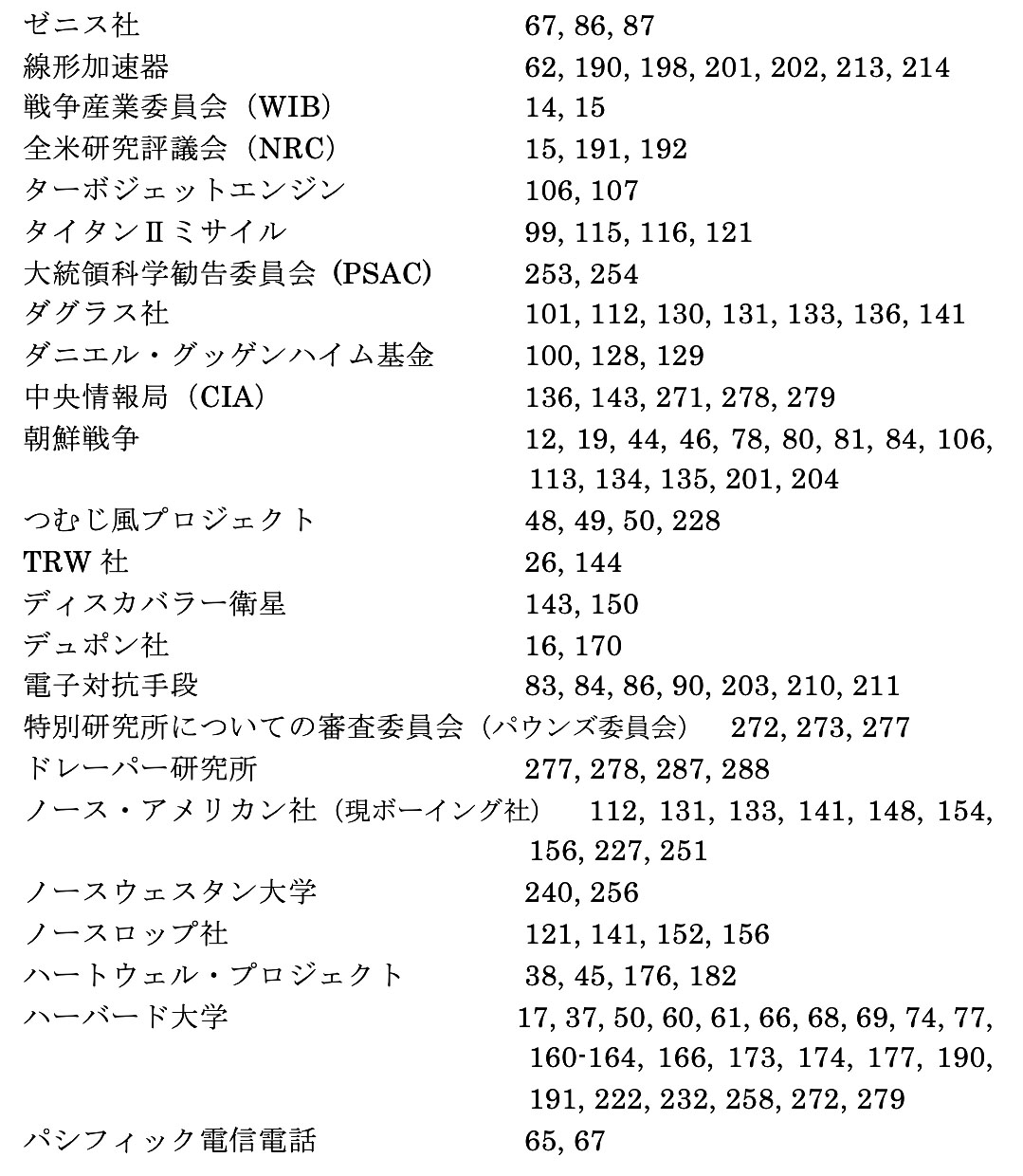

1.事項索引に24項目の記載漏れがありました。お求めされた方にはたいへん申し訳ありません(2/18)。以下に画像イメージ(クリックで拡大)、PDF、ワードファイルをご案内します。PDFとワードファイルは書籍と同じA5サイズにしています。

---------------------

2.日本語版への序文(本書9〜11ページ)のオリジナル(英語)

(下に続きます。)( 日付は2020年9月24日です。)

日付は2020年9月24日です。)

3.9章に出てくる「3月4日のマニフェスト」の日本語訳(2020年12月31日既報)

4.本に出てくる組織や人物の関係を図式に整理していますので、内容のチェックの一助に、またはお読みになるときに参考にして下さい。ただし翻訳作業の便宜のために作成したもので、正確性や網羅性を保証するものではありません。(2020年12月31日既報)

5.訳者あとがき(371ページ)の英訳

6.「腰巻き」部分の英訳/English translation of phrases on obi (wraparound band)

front (left, bottom)

How did US scientists get incorporated into military research?

back (right, bottom)

Most of the books published in Japan on the theme of the relationship between war and scientists are about the development of the atomic bomb or about prominent scientists.

This book is a documentary about military research from World War II to the US-Soviet Cold War at two famous universities in modern America, both individually and organizationally. Few well-known scientists outside the scientific community appear. It is clarified in detail how "ordinary" researchers, although they belong to the prestigious universities of MIT and Stanford, have been incorporated into military research.

(原書タイトル:The Cold War and American Science ―The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford, 著者:Stuart W. Leslie)

全国の図書館101館で所蔵(2022/1/18現在)

目次

1.事項索引の追加(すぐ下)/the addition to the subject index

2.日本語版への序文のオリジナル(英語)/preface to the Japanese edition in English

3.「3月4日のマニフェスト」の日本語訳(リンク)/Japanese translation of the 'March 4 manifesto →直接ジャンプ

4.組織や人物の関係を図式にしたもの(リンク)/relationships of organizations →直接ジャンプ

5.

6.

-------------

1.事項索引に24項目の記載漏れがありました。お求めされた方にはたいへん申し訳ありません(2/18)。以下に画像イメージ(クリックで拡大)、PDF、ワードファイルをご案内します。PDFとワードファイルは書籍と同じA5サイズにしています。

---------------------

2.日本語版への序文(本書9〜11ページ)のオリジナル(英語)

(下に続きます。)(

Author’s Preface

This book needs an epilog more than it needs a preface. With the end of the Vietnam War, and the beginning of the “war on cancer” and other health initiatives, funding patterns changed significantly at MIT and Stanford, as they did for the country as a whole. Department of Defense-sponsored research dipped both absolutely and as a fraction of their research budgets, falling by half from 1967 to 1977. By 1978 the Department of Energy (which includes the US national weapons laboratories) had become MIT’s biggest sponsor, followed closely by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. The Department of Defense dropped to fourth. MIT nonetheless remained atop the list of the nation’s leading university defense contractors, even after the divestment of Draper Laboratory and Lincoln Laboratory. From 1974 to 1984, MIT ranked first for all but two years, averaging $17 million a year in Department of Defense spending. Stanford, too, received relatively less funding from the Department of Defense and more from the Department of Health and Human Services, including the National Institutes of Health, NASA, and other civilian agencies.

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a ballistic missile defense program announced by President Ronald Reagan in 1983 and popularly dubbed ‘Star Wars,’ reopened the debate about military and classified research on campus. Though never operational, SDI pumped $30 billion for research and development into industrial defense contractors, national laboratories, and universities. In 1985 a group of MIT faculty members, apprehensive about the long-term consequences of the SDI, met with MIT President Paul Gray and subsequently organized itself as the Ad Hoc Committee on the Military Presence at MIT. Chaired by political scientist Carl Kaysen, the committee surveyed MIT faculty and students to gauge their response to the Reagan-era military build-up and the SDI contracts. A surprisingly high response rate—45 per cent of the faculty, 17 per cent of the graduate students, and 20 per cent of the undergraduates participated in the survey—suggested genuine interest in the subject.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the committee asked the MIT Office of Sponsored projects for a list of SDI-funded projects on March 4, 1985, the sixteenth anniversary of the day of reflection in 1969. The survey results indicated widespread concern about SDI’s potential impact on MIT, starting at the top. President Gray himself addressed the matter at commencement that spring: “What I find particularly troublesome about the SDI funding is the effort to short-circuit the debate and use MIT and other universities as political instruments in the attempt to obtain implicit institutional endorsement. This university will not be so used.” A majority of the faculty agreed with Gray’s further statements: ”SDI funding should be avoided because MIT funding should not be involved in weapon system development.” And they strongly opposed classified research and security clearances for graduate students, foreign and domestic, as antithetical to the tradition of academic freedom. Students did not take to the streets as they had in 1969, although significant numbers of graduates in the class of 1985 (45 per center in electrical engineering and physics, 27 per cent in mechanical engineering, and 21 per center in aero and astronautical engineering) said they “felt strongly against working in defense.”

Stanford, too, had a different response to participating in SDI than it had had during most of the Cold War. Many of its faculty and graduate students opposed SDI and the university accepted just $3 million in SDI contracts, far below a number of other universities, including Utah, Texas, Georgia Tech, and Johns Hopkins. Stanford’s most important contributions to SDI came from its on-campus think tanks. Edward Teller, often considered the father of SDI, became its most forceful advocate as a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. Physicist Sidney Drell, deputy director of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, founded the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford and it became an influential voice on nuclear weapons policy, including SDI.

Nowadays MIT and Stanford must wrestle with yet another round of military contracts in support of the global war on terror. The subspecialties have changed, to surveillance, computer and information security, cryptography and related fields, but the fundamental issues about MIT’s “service to the nation and service to humanity” (the university’s official mission statement) raised by faculty and students during the late 1960s and early 1970s remain the same. The research portfolios of MIT and Stanford are far more balanced now than they were at the end of the Cold War. In 2019 MIT received just 18 percent of its budget from the Department of Defense and another 9 percent from the Department of Energy, compared with 10 percent from the National Science Foundation, 17 percent from the National Institutes of Health, and 22 percent from industry. Stanford has similarly moved away from its reliance on military funding to a mix of federal funding agencies. In 2017 it received $85 million from the Department of Defense, but $75 million from the National Science Foundation, $23 million from the Department of Energy, and $493 million from the Department of Health and Human Service, including NIH, and 9 percent from industry. Stanford ranks seventh among American universities in NIH funding and MIT ninth.

Defense spending, then, remains a significant though no longer predominant source of research funding for both MIT and Stanford, and continues to shape the priorities of key science and engineering fields. If those priorities are an important legacy of Cold War science, so too is the spirit of critical inquiry that gave birth to the Union of Concerned Scientists at MIT in 1969. Learning how to make informed and socially responsible decisions has become a hallmark of the science and engineering curriculum, no more so than at MIT and Stanford themselves.

3.9章に出てくる「3月4日のマニフェスト」の日本語訳(2020年12月31日既報)

4.本に出てくる組織や人物の関係を図式に整理していますので、内容のチェックの一助に、またはお読みになるときに参考にして下さい。ただし翻訳作業の便宜のために作成したもので、正確性や網羅性を保証するものではありません。(2020年12月31日既報)

5.訳者あとがき(371ページ)の英訳

Translators’ afterword

Most of the books published in Japanese on the theme of the relationship between war and scientists are about the atomic bomb development or about famous scientists, but not much else. This book is a documentary depicting military research mainly in postwar era at two famous American universities from both an individual and organizational perspective. Few prominent scientists, as commonly known outside the scientific community, appear. The book is a detailed account of how ordinary researchers were automatically incorporated into military research.

As the title suggests, this book focuses mainly on the Cold War period of the US and Soviet Union, but it also includes the period that overlaps with the Manhattan Project during World War II before that. One of the research projects depicted is the development of radar. At that time, the Radiation Laboratory, as described in Chapter 1 of this book, had 4,000 employees, an annual budget of $ 13 million, and contracts with industry of $ 1.5 billion, which was on par with the Manhattan Project (the cost of the Manhattan project was about $2 billion, and the Los Alamos Institute, which was the center of the project, eventually had 6,700 staff).

It is natural that many books dealing with the relationship between the atomic bomb and scientists have been published in Japan, since Japan is the only country to have been attacked by the A-bombs. However, radar is the most important technology that contributed to the victory of the United States and the Allies, including the US-Japan War. Therefore, a brief mention of this history of development in this book may fill much of the knowledge gap of Japanese people about the history of military technology.

But above all, the current significance of this book, especially in our country, is the fundamental fact-based question of the relationship between universities and the military. Japan's academia has issued a "Statement of disobeying science for war" as the Science Council of Japan in 1950 in response to reflections from scholars' cooperation in a reckless and catastrophic war. It is, so to speak, "Article 9" in the academic world. Until today, this principle has not been violated at universities, and the places where military research and weapons development are conducted are limited to industry, and the scale is not large.

However, over the last few years, there are moves in Japan to introduce funds from the Ministry of Defense to universities. Although the number of cases and the amount of money are limited so far, the budget cut of the running costs of universities, which should be called the university impoverishment policy by the Ministry of Education, will cause researchers to gradually shift to funds related to the military. It is, so to speak, an economic conscription system for academics. This book gives an important warning about what kind of world it will take us to. In that sense, despite the fact that 27 years have already passed since the original edition was published, this book seems to have special and contemporary meaning in our country.

Weapons are the product of technology developed solely for the purpose of killing people. The activities carried out in the laboratory by weapons system researchers and developers are undeniably intelligent, and no one is killed or injured there. But the purpose of their work is to create good individual weapons and their systems, in other words to provide someone with the most efficient means of killing people. Researchers do not commit murder directly, but the "accomplice relationship" with those who use weapons directly is clear.

In this way, weapon system development = military research is a violent act in a broad sense because there is an event of murder at the end point straight ahead. So the name "intellectual violence" is appropriate for this activity. Not only do we hope that this violence will not go into full swing in our country, but we also want to aim for a future in which it is banned worldwide.

When one of the translater (Toyoshima) came up with the idea of translation, Professor Takehiko Hashimoto of the University of Tokyo, who was once researched under the author Professor Leslie, gave me various consultations and guidance. We asked Professor Yubun Suzuki of Kyushu University to translate the text of Thorstein Veblen, the door at the beginning of this book. We would like to take this opportunity to thank them all. The author, Professor Leslie, always kindly and politely responded to the repeated questions of the translators in translating, especially in spite of the difficulty and busyness of his university at work during the corona crisis. We are also very grateful for the excellent preface he wrote for this book. We would like to thank everyone at Ryokufu Shuppan for their advice and proofreading.

6.「腰巻き」部分の英訳/English translation of phrases on obi (wraparound band)

front (left, bottom)

How did US scientists get incorporated into military research?

back (right, bottom)

Most of the books published in Japan on the theme of the relationship between war and scientists are about the development of the atomic bomb or about prominent scientists.

This book is a documentary about military research from World War II to the US-Soviet Cold War at two famous universities in modern America, both individually and organizationally. Few well-known scientists outside the scientific community appear. It is clarified in detail how "ordinary" researchers, although they belong to the prestigious universities of MIT and Stanford, have been incorporated into military research.

2021-02-18 16:04

nice!(0)

コメント(0)

9条守ろう! ブロガーズ・リンク

9条守ろう! ブロガーズ・リンク

コメント 0