日経サイエンスのスティグリッツ教授の文章 [社会]

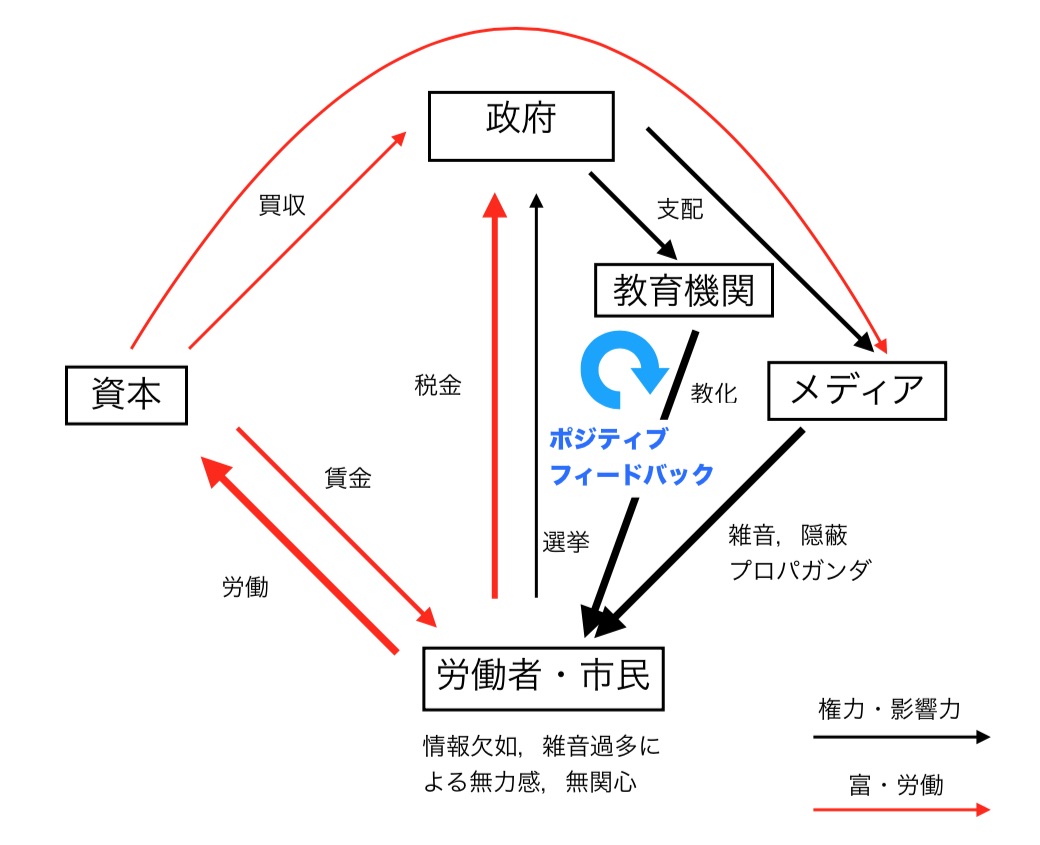

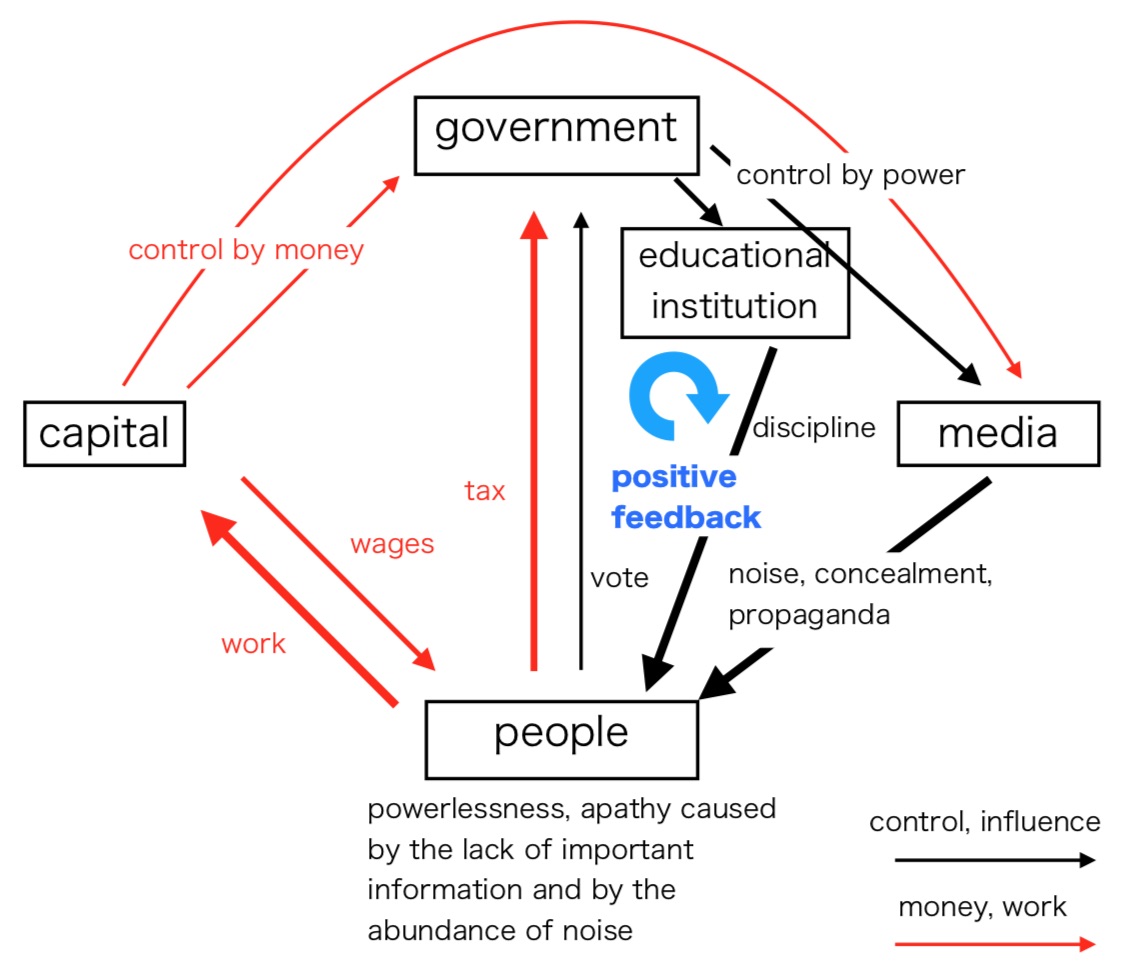

「先進諸国」の一つであるはずの日本で民主主義が機能していない原因、メカニズムについて、当ブログでは、金・メディア・教育・政治権力が絡む「正のフィードバック」の問題を図式化して提起してきました。例えば次の記事です。

「先進諸国」の一つであるはずの日本で民主主義が機能していない原因、メカニズムについて、当ブログでは、金・メディア・教育・政治権力が絡む「正のフィードバック」の問題を図式化して提起してきました。例えば次の記事です。「平和研究集会での発表から」の

社会のメカニズム図式化の部分

これと同じような議論を、ノーベル経済学賞の学者、ジョセフ・スティグリッツ教授の文章に見つけました。「日経サイエンス」5月号の「仕組まれた経済 格差拡大の理由」という6ページにわたる論文です。ただ、私のは政治的・社会的問題の「定性的な」な分析ですが、スティグリッツ教授のは経済の面での定量的な分析です。

(

その、該当部分を引用します。

(ピケティの『21世紀の資本』の議論を批判した後)経済中心と社会一般的という違い、定量的と定性的という違いはあるものの、従ってメディアや教育については触れていないものの、「フィードバック」というキーワードに我が意を得たり、と思った。やはり同種の問題に当然専門家は気づき、分析していたわけだ。もしかすると教授は当ブログ該当部分の英語版を読んだのかも(笑)。

ある別の理論のほうが事実にずっとよく一致する。1970年代半ば以降,経済ゲームのルールが世界レベルと国レベルの両方で書き換えられ,富裕層が有利になり,その他は不利になった。そして米国のルールはすでに労働者に冷たかったにもかかわらず,この誤った方向へル一ルがさらに書き換えられてきた。この見方に立つと,経済的不平等の拡大は選択の間題であり,政策と法律,規則の結果だ。

米国では他の先進国に比べてそもそも強かった大企業の市場支配力が,どこよりもさらに強まった。その一方で,他の先進国よりも弱かった労働者の市場支配力がさらに弱まった。これはサービス産業経済への移行だけが原因ではない。ゲームのルールが仕組まれていたからだ。ある政治システムによってルールが定められ,その政治システム自体もゲリマンダー(偏った選挙区割り)とボーター・サプレッション(ライバル支持者が投票に行かないように誘導する組織的な投票妨害),金権によって仕組まれている。悪循環が生じている。経済的不平等が政治的不平等に形を変え,それが金持ちを優遇するルールにつながり,これが経済的不平等をさらに強めている。

金力と政治力のフィードバック

ある政治システムにおいておカネが政策に影響を及ぼし,経済的不平等を政治的不平等に転換する道筋が,政治学者によって詳しく記録されてきた。富裕層がその政治力を用いてゲームのルールを自分たちに有利なように変えるにつれ(例えば独占禁止法を緩める,労働組合を弱くするなど),この政治的不平等は経済的不平等をさらに大きくする。私を含め経済学者は数理モデルを用いて,おカネと規則の間のこの双方向フィードバックが働く結果として,少なくとも2つの安定状態が生じることを示した。経済的不平等が小さな状態からスタートした場合,政治システムはその状態を維持するようなルールを生み出し,不平等の小さな平衡状態に至る。これに対し,米国のシステムは不平等が拡大するもう1つの安定状態にあり,その状態は民主的な政治が目覚めない限り今後も続くだろう。

ルールがどのように形成されてきたかを説明するには,独占禁止法から話を始める必要がある。米国で独占禁止法が立法化されたのは128年前で,市場支配力の集中を防ぐのが目的だった。しかし,その執行は弱められてきた。技術の変化によって少数のグローバル企業が市場支配力を握るようになり,実際にはむしろ執行を強化すべき時代なのに。

"Positive feedback" mechanism paralyzing our democracy

なお、私の「正の」フィードバック、という言い方はやや言葉としての厳密さを欠いたかも知れない。教授の「安定状態」「平衡状態」(私の「ロックされた状態」に該当)に向かう、というのが正しい用語法だろう。

図式の日本語版と英語版を再掲します。

An alternative theory is far more consonant with the facts. Since the mid-1970s the rules of the economic game have been rewritten, both globally and nationally, in ways that advantage the rich and disadvantage the rest. And they have been rewritten further in this perverse direction in the U.S. than in other developed countries—even though the rules in the U.S. were already less favorable to workers. From this perspective, increasing inequality is a matter of choice: a consequence of our policies, laws and regulations.

In the U.S., the market power of large corporations, which was greater than in most other advanced countries to begin with, has increased even more than elsewhere. On the other hand, the market power of workers, which started out less than in most other advanced countries, has fallen further than elsewhere. This is not only because of the shift to a service-sector economy—it is because of the rigged rules of the game, rules set in a political system that is itself rigged through gerrymandering, voter suppression and the influence of money. A vicious spiral has formed: economic inequality translates into political inequality, which leads to rules that favor the wealthy, which in turn reinforces economic inequality.

Feedback Loop

Political scientists have documented the ways in which money influences politics in certain political systems, converting higher economic inequality into greater political inequality. Political inequality, in its turn, gives rise to more economic inequality as the rich use their political power to shape the rules of the game in ways that favor them—for instance, by softening antitrust laws and weakening unions. Using mathematical models, economists such as myself have shown that this two-way feedback loop between money and regulations leads to at least two stable points. If an economy starts out with lower inequality, the political system generates rules that sustain it, leading to one equilibrium situation. The American system is the other equilibrium—and will continue to be unless there is a democratic political awakening.

An account of how the rules have been shaped must begin with antitrust laws, first enacted 128 years ago in the U.S. to prevent the agglomeration of market power. Their enforcement has weakened—at a time when, if anything, the laws themselves should have been strengthened. Technological changes have concentrated market power in the hands of a few global players, in part because of so-called network effects: you are far more likely to join a particular social network or use a certain word processor if everyone you know is already using it. Once established, a firm such as Facebook or Microsoft is hard to dislodge. Moreover, fixed costs, such as that of developing a piece of software, have increased as compared with marginal costs—that of duplicating the software. A new entrant has to bear all these fixed costs up front, and if it does enter, the rich incumbent can respond by lowering prices drastically. The cost of making an additional e-book or photo-editing program is essentially zero.

2019-04-05 11:05

nice!(0)

コメント(0)

9条守ろう! ブロガーズ・リンク

9条守ろう! ブロガーズ・リンク

コメント 0